Absent Friend 2: Nikolaj Bruus of Quiet Sonia, My Tjau is Kapow

About growing up post-rock in the Danish 2000s, at least two very inspired bands that never made releases, the Lo-Fi Festival, and more.

Nikolaj Bruus runs Pink Cotton Candy Records and is the songwriter behind the septet Quiet Sonia. Their first LP QS was released two years ago, now. QS was an exploration of acoustic tonality, analogue fidelity, and room-recording. Quiet Sonia’s faithfulness, there, to an idea of recording authenticity (as Nikolaj’s copy puts it, a “fragility”) stands in counterpoise to their raucous exhibition of studio treatment on Wild and Bitter Fruits. I won’t claim that this interview does justice to Quiet Sonia, it instead spirals into an investigation of the indie scene in Odense, in the 2000s and early 2010s.

I knew Nikolaj would be an interview for Absent Friend when I listened to the album he made with his childhood friends in Odense, over the last 20 years, beginning in the 2000s, especially in a group called My Tjau is Kapow. This band can barely be found online, only observable through stray statements made over the years, and The Pink Sea, their sole album, which Nikolaj actually finished mastering in April.1

Nikolaj kindly allowed me into his apartment living room in Frederiksberg for this interview. Frederiksberg is in Copenhagen, which I’ll deign to write as København.2 We talked for a long time all said, walked through the cemetery up to Nørrebrogade, down into the earth, over to the German bar where I met Tobias Frank (also of My Tjau is Kapow).

This writing answers about a thousand questions that I suppose very few people were asking. The matter is that I think just about everything Nikolaj said to me is worth sharing with you. Nikolaj’s life, as I had hoped, offers a window into both independent (post-)rock and alternative electronic culture in Denmark, which I’ve tried and struggled to find any decent writing about. Now there’s this, presented out of order and with interjection.

A. Friend: I notice you've only put the My Tjau is Kapow material up through your own label, did you guys have it online when you were a band?

Nikolaj: No, no..

A. Friend: So you all never put music online?

Nikolaj: I think we had a very early version of the track “The Pink Sea.” It's actually the early version that also ended up on the release, because we lost the recordings of 2015-2017, such a shame, that was the track that evolved the most. We had lots of Remain in Light influence, playing live synth solos and bongos and stuff like that and … we lost everything.

[[we both laugh]]

That's just the way it is.

But there's also a very cute and kitschy, naive feeling about the first version of it, I think. It would make better sense with the other material if “The Pink Sea” was also the updated version, but whatever.

A. Friend: Did you guys manage to play in Odense?

Nikolaj: We often would, actually, play with other musicians as well, as a bigger band, and we would dub more acoustic and organic elements on top.

We had, for instance, Jens Aagaard3 - Tettix Hexer - playing with us, he's a very great musician. But My Tjau is Kapow evolved from this post-rock band called Sunn Paw — I had something with these pows, very funny and strange bands names.

I think ‘My Tjau is Kapow,’ I wouldn’t use that name today. I was so young and innocent, I didn't at all realize that it could have some sort of sexual connotation to it. But it also could be a broken scooter, or something.

A. Friend: Does it mean something?

Nikolaj: It doesn't mean anything. But it could.

Nikolaj: The next Quiet Sonia record is going to find a middle way.

Which… I've known from the beginning that the middle way would be the best way. But I needed to experience the other things, personally, before I could really see it and do it.

I read a lot about how Bruce Springsteen recorded Darkness on the Edge of Town, that album, which has, to me, the perfect balance between live recording and studio approach. I'm trying to copy some of his techniques for the next LP.

A. Friend: As directly as possible?

Nikolaj: I don't know. Probably not, because we don't sound very much like Bruce Springsteen.

[[We both laugh, and we cut the interview off there.]]

A. Friend: So when did you pick up guitar?

Nikolaj: I started playing guitar when I was around seven. I think I went to a very liberal, progressive, left-wing school.

[ … / … ]

A. Friend: Was it a folkeskole4 you went to?

Nikolaj: No, I was in a private school. My girlfriend, who is a folkeskole teacher now, she really doesn’t approve of the private school.

A. Friend: The school that you were saying was alternative - it was a private school?

Nikolaj: Yes .. I mean.. we grew up singing- you know Christiania? [- Yeah. -]

We grew up singing these Christiania songs.. like ‘You can't hit us, you can’t kill us.’ [“I kan ikke slå os ihjel.”] .. or stuff like, uh, ‘Atom bombs, atom bombs, you can kill yourself.'5

A. Friend: Oh, my mom’s given me all these like pictures of her mom marching in atomkraft marches.

Nikolaj: Yeah. I really think I'm getting a better and better understanding of how I'm shaped, today, by that school, because the teachers were all folk musicians. They’d play old Danish and Swedish songs.

A. Friend: So, who is the Bob Dylan of Danish Folk?

Nikolaj: [[instantly, confidently]] That's Poul Lendal.6 He's a grand.. legendary fiddle player. He was also the headmaster of the music conservatory’s folk line.

A. Friend: Do you like Danish folk song, is that an interest to you?

Nikolaj: Well, I don't .. [[laughs]] I don't want to .. [[his eyes shift to my recorder]] to make anyone angry now .. I don't think that Denmark has the strongest folk music tradition. It's much stronger in Norway, and Sweden.

[ … / … / … ]

As to whether there are specific folk music traditions, .. on the island of Fanø, they have their specific folk music traditions, special ways of dancing and dressing…7

A. Friend: Well, at least that’ll be hyperlinked.

A. Friend: You formed a group with four friends.

Nikolaj: So, from all the improvisations in our school breaks, we formed. This is a funny part - I think the first month we were a cover band of The Hives ..

A. Friend: I didn't want to ask, like, ‘as a Dane, were you thinking about what the Swedes are doing?’

Nikolaj: [[laughing]] Yeah, so apparently we thought about what the Swedes were doing. But then, things happened very quickly back then, after a month we thought The Hives were trash, and we were into Sonic Youth and My Bloody Valentine.

A. Friend: For sure.

Nikolaj: Yeah, we figured it out.

We started making our own indie rock songs, you know, a couple of months happened again, we went to the local music library all the time, and filled up like three bags with CDs.

A. Friend: You know, I left from there this morning.8

Nikolaj: Ah, but you know, that’s the new place, this was the old place9 .. the old place was massive, and it was only a music library. They must have had some employee who was a musical genius because on display was, like, experimental IDM, and chamber classical music, and everything.

A. Friend: They’re like ‘welcome to the music library, do you want Aphex Twin or Arvo Pärt?’

Nikolaj: Exactly, exactly. And always the newest stuff, also, from the best labels and I would just basically fill up some bags, and I would perhaps just look at the cover, or the label, or I would go to one of the computers, and I would always use allmusic.com back then.

[ … / … ]

A. Friend: So you were practicing guitar for six, eight, or even ten years before you guys started playing together as teenagers...

Nikolaj: Yeah, I mean the noise rock stuff happened when I was around 12.10

My friend Jonatan [K. Magnussen], he and I would always play together and honestly compete a bit, trying to be better than the other. He later on formed the jangle-pop band Balloon Magic,11 which later on became the more aggressive post-punk group Love Coffin, and now he plays in Chopper. [...]

He would prefer Daydream Nation, you know, I would prefer Sister. I would prefer Bark Psychosis, and he would prefer Slowdive.

A. Friend: I’m with you.

Nikolaj: I guess the reason why [Jim O’Rourke] wants to stay in Tokyo is because, I think, it's the only city on earth that has such a vibrant experimental, improvised music scene. They have huge record stores that only sell ambient, noise, industrial. They actually buy me and my friends’ tapes, stuff like that, and they just pay up front. Nobody else does that. I love Japan.

A. Friend: Like Quiet Sonia- they bought up that?

Nikolaj: I only just discovered, um, Tobira Records, like half a year ago,12 he [Taka from Tobira] ordered basically everything from Pink Cotton Candy. My friends who have a label called Kornmod, which is a fantastic label, -

A. Friend: You said my friends? Are the Kornmod folks people you went to school with, or people that you've met in Kobenhavn?

Nikolaj: Well, the primary force is one member, who's also from Odense, Jonas Torstensen, like .. there's interviews with him from when he's like eight years old, on the internet,13 where he already has very strong opinions on Krautrock and stuff like that. He’s blind, I think, born blind .. he's one of the biggest music nerds on this planet. I didn't know him, back then, but I realized many years later, when he started Kornmod .. he knew everything I've ever been involved with. Like, projects nobody else had. I would say there's no substitute for learning about Danish music than go to him. He's the greatest and he knows.

I think he also has a very impressive knowledge of early Danish psych rock, that's also a specialty. But today Jonas is doing, if you ask me, like, the best ambient that has ever been put out in Denmark, I think it's better than [[- Nikolaj notes to me that he hopes we can cut out some of these judgmental statements in editing ]] - I think it's better than the English, all the other kinds of more popular ambient ...14

Jonas is very, very, very important.

A. Friend: I was really excited when I finally found out about Kornmod. […] I guess this is kind of a non-question, because there’s no real, operative definition of ambient - because much like [Simon Reynold’s idea of] post-rock, Brian Eno’s definition doesn’t work - but have you tried making ambient?

Nikolaj: Well I often integrate, like, ambient passages, and I thought about maybe doing sort of a, like Windy & Carl ambient sound, or Kyle Bobby Dunn style, based on the electric guitar.

A. Friend: I feel like there's no boundary between, in philosophical terms, what's denoted when somebody says ambient and what's denoted when somebody says sound art, it's the same container, but with two labels on it.

Nikolaj: Often I think, when I read genre descriptors, I often think of sound art as something more like musique concrete, or field recordings, with ambient being something that's made with harmonic and melodic elements, but not necessarily …

A. Friend: Ambient is the sound art made with instruments?

[[We both start laughing]]

I guess that’s it, yeah, that’s the divide.

Nikolaj: I’m generally very skeptic about this division, sound art in general, or fine art, or-

A. Friend: Well, for one thing art doesn't really work as a word.15

Nikolaj: It's very deeply entrenched in Denmark, in the way the cultural economy works, that there's a boundary, whatever is labeled art music .. there’s a lot of state support for it. But what if you're playing .. [- Cultural music. -] Yeah, what if you’re playing experimental forms of so-called popular music. You're left in a no-man's land. Nobody wants to buy it and listen to it, you don’t get state support. It's just a very old school way of thinking.

A. Friend: Rock comes out of these rhythmic traditions that come out of the blues, so once rhythm gets pulled out … post-rock has always often been somebody doing the splits between these two separated things, non-rhythmic and rhythmic music. Some people will call Hex “ambient rock,” though progressive rock already smudged away this boundary..

Nikolaj: There's at least one track on Hex which is decidedly ambient, .. I guess that’s a great explanation of post-rock, there, but when I got into it, I remember people saying that it went into two different directions. Slint on the one hand, Talk Talk on the other hand … I would also think of Tortoise as a third way.

Nikolaj: I was a massive, massive Pink Floyd fan, around 10 years old. I think they were my first introduction to a more progressive, experimental rock and became a natural entryway into post-rock later on.

A. Friend: [[Betraying that I think Bark Psychosis were, in a pretty real sense, a prog rock band]] Oh, when did you first hear Bark Psychosis?

Nikolaj: Oh, yes. I was 13 years old and, in Denmark we have something called confirmation16 …

A. Friend: I was in a store in Aarhus the other day. It was full of, shoulder-to-shoulder, 10-year-olds with fades. The woman working there said ‘it's Blue Monday, they all had confirmation yesterday, and they all have $1,000 today.’

Nikolaj: Yeah, actually what I had was .. a lot of people hate this concept at home, but .. a non-formation. [[I laugh]] It was like .. a Christian event, but, .. I wasn't ready to dedicate myself to a life in service of God when I was this age. Even while the priest came to my house and tried to convince me otherwise.17

[[- I tell Nikolaj I was agnostic at 11, Buddhist at 14. -]]

But still, you know, it's nice to hold some sort of, even though you don't believe in religious stuff, you can still have rituals and traditions and stuff in society. So we held a party. My parents have a friend called Claus Falkenstrøm, who was a music journalist for a very great, smaller, niche, independent sort of site called Geiger18- Aarhus based, they wrote on all the greatest, best, experimental alternative rock music, and other sound experiments. About international releases as well, but written in Danish.

I mean, if you're trying to get into Danish..

A. Friend: Did he get you into, like, Under Byen? [- Yeah. - ]

Speaker Bite Me?19 [- Yeah. -]

Bows?20 [- Yeah. -]

I love Bows. [- Yeah.. me too. -]

Have you met her, Signe [Høirup Wille-Jørgensens]?21

Nikolaj: Actually, she's been my teacher at the Rhythmic Music Conservatory as well22 .. I also talked with Luke Sutherland.23

A. Friend: Wow.

Nikolaj: His Music A.M. project24 is one of my favorite projects in the world. I'm a massive fan of his work.

A. Friend: So you had a family friend who showed you Bark Psychosis- can you rattle off who else comes to mind when you think of Claus [Falkenstrøm]?

Nikolaj: Well, he made a mix tape CD for me. Lots of great stuff on it, I think Electrelane25 and Destroyer26, lots of stuff, but he bought me, for my nonformation, Codename: Dustsucker on vinyl.

And it came with a funny story, Dustsucker had just come out [2004] - if you're Danish speaking, or know anything about Danish musical culture, this is pretty funny - he said that I was on a waiting list, and the only person above me on the waiting list was Mikael Simpson, and he's a pretty famous-27

A. Friend: [[thinking of an album I like]] What’s that one with his face on it?

Nikolaj: [[Without the faintest delay, and spoken so quickly it scares me]] That’s Os 2 + Lidt Ro. He was quite inspired by slowcore and post-rock.

A. Friend: What does Os 2 remind you of?

Nikolaj: It reminds me of all these stories about him, at that time, his self-promotion, that he lived in a small apartment, always awoke at night, living with his cats and recording in the bedroom.28 A very specific sort of Scandinavian melancholy, that was also present in Efterklang and a lot of the other names in the early 2000s.

[ … / … / … / … / … / I bog down our conversation by telling him about the term “post-britpop,” he tells me in Denmark they called it ‘crying-rock.’ ]

So, yes, I got the Bark Psychosis record, and I put it on at home on my turntable.

I just remember I was completely, like, paralyzed. Turning the levels up so high and going almost down on my knees in front of the stereo. This was the most beautiful music I'd heard in my entire life.

Once I read about Graham Sutton having the same experience with Talk Talk, back in the day.29

I still think that I love Hex but, Codename is perhaps the most accomplished piece of indie rock made to date. Both in terms of composition and songwriting, also in terms of production. Such a warm, wonderful, analog quality to it, but still an immense amount of clarity and detail. I really want to hear someone try to do that again.

I mean there were about 10 years from Hex to Codename, and then around, I think it was around 2014 or 2015, there was talk of a new Bark Psychosis album, which would’ve made sense, considering the time stretches, but it never happened. We're still waiting. Now he's producing for Rough Trade, I think he's hired as a freelance engineer, doing stuff for bands like British Sea Power.30 I'm very curious about, right now, he's doing a record with These New Puritans, who took a sharp and dramatic to suddenly completely embrace this very small niche of Talk Talk and Bark Psychosis sounds.31

We're [Quiet Sonia] doing a new record together, and I heard the first single, and .. it sounds like a 2025 version of Bark Psychosis, basically.

A. Friend: It’s such a magic thing about post-rock that when I see it being said, I actually don't know which one it's gonna be. The Godspeed worship, the indie rock that Epic45 and Bark Psychosis do …

Nikolaj: Of course today, when someone hears ‘post-rock,’ they think of this very - excuse my language, - vulgar, and sentimental, youtube-meets-metal-meets-Sigur-Rós kind of thing.

A. Friend: Yeah, well, today and for the last 20 years.

[[Nikolaj goes to refill both our coffee cups.]]

Denmark’s middle island, Fyn, is certainly socially devalorized moreso than it is peripheral to Denmark.

I came in to meet Nikolaj from Odense C, where I’d awoken in my aunt and uncle’s home. Odense banegården [trainyard] has stayed the same since I was a child, basically, except that there’s now a ‘Nordic film theatre’ in the place where there was once a cybercafe, where my cousin Ditlev introduced my brother and I to a game called Starcraft 2.32

Odense is the largest city on Fyn, it’s a classic Fjord-port city (the port, which I’ve just learned is Denmark’s only canal-harbour, is active and due for expansion, my uncle told me at dinner), they just added a light-rail line in town, though the city also sprawls radially in all directions except those enclosed by harbor and fjord, they recently attracted Denmark’s by-far largest corporate entity to construct their newest offices there (my uncle reasoned, at dinner, that this is perhaps, in essence, because Denmark’s population distribution has become too clustered in København, which has made that city a cultural hotbed and a vacuum for minor populations and immigrants, yes, but also creating a housing crisis in which the merchant harbor’s rent prices have soared, in the last two decades, relative to increases in purchasing power, in spite of some excellent regional rail lines), and the tourism department of the city would like me to point out that it’s where Hans Christian Andersen called home, even though the mermaid is instead in København, for some reason.

Denmark obeys at some level a cultural superiority-inferiority complex in which even the largest non-København cities are treated as though they’re arbitrarily far off into the countryside.33

When my mother grew up on Fynen - in a village of which Danes are willing to accept my ‘et lille landsby nær Faaborg’ as a totalizing ontic treatment, vaporizing any need for further questioning - the map of Denmark had a significant crease in the form of the Storebælt, the waters separating Sjælland and Fynen. You used to cross the Storebælt by water, until the year I was born, 1998.

Accordingly, and as much is obvious to a Dane - but perhaps not so much to an American, as I remember being surprised to have heard this from my mother, who lived four decades under the yoke of this tired fact -, the Storebælt needed to be crossed by ferry. For drivers, this was done by their automobiles boarding the deck of the ferry. The typical form of a roadway-to-roadway transit ferry such as this is to have a top-deck inaccessible to passengers, a passenger deck (flooded with light with large observatory windows), and below this a tremendous automobile deck (in which one is also perhaps afforded the option to sit in a shaking, gray room, in a powered-off vehicle instead of joining the hordes in the lightroom or salty air). Until the bridge was built, the Sjælland-Fyn ferry also served the railway/s on the two tremendous islands, meaning that railcars would also slot onto what I’ve called the automobile deck.34

In Denmark the sky is calico, and the distance from rain to shine is measured in minutes. The intercity line from Odense C to København H [Hovedbanegård, literally head-trainyard] is measured in hours, barely. One hour and one minute, in my experience.

Is any part of me prepared to say that the literal logistical frictions created by these waterways (detouring to the ferry docks, of course the incidental time waiting for the scheduled departure, which may evolve into hours spent hoping for sheets of ice to be cleared, and then the relevant ferry ride, which would be less than an hour in any case) play a causal role in the quirks of Danish culture, the animosity between the three major Danish island-forms, and the specific forms of DIY culture that have emerged in the state, unlike the Swedes, being as they are so slightly more successful in indiepop and rock, or the Norwegians, originators of mankind’s most iconic and searing expression of metallic godlessness?

Ah, no, perhaps all that’s a reach.

It’s beautiful, anyway, the ferry rides are, at least when the sun shines. I kinda wish my trip to the capital would’ve taken longer.

A. Friend: Did you visit Struer as a kid?

Nikolaj: My mom actually grew up in Struer. When we moved around a bit, I was quite a lot in Struer, in the summer locations.

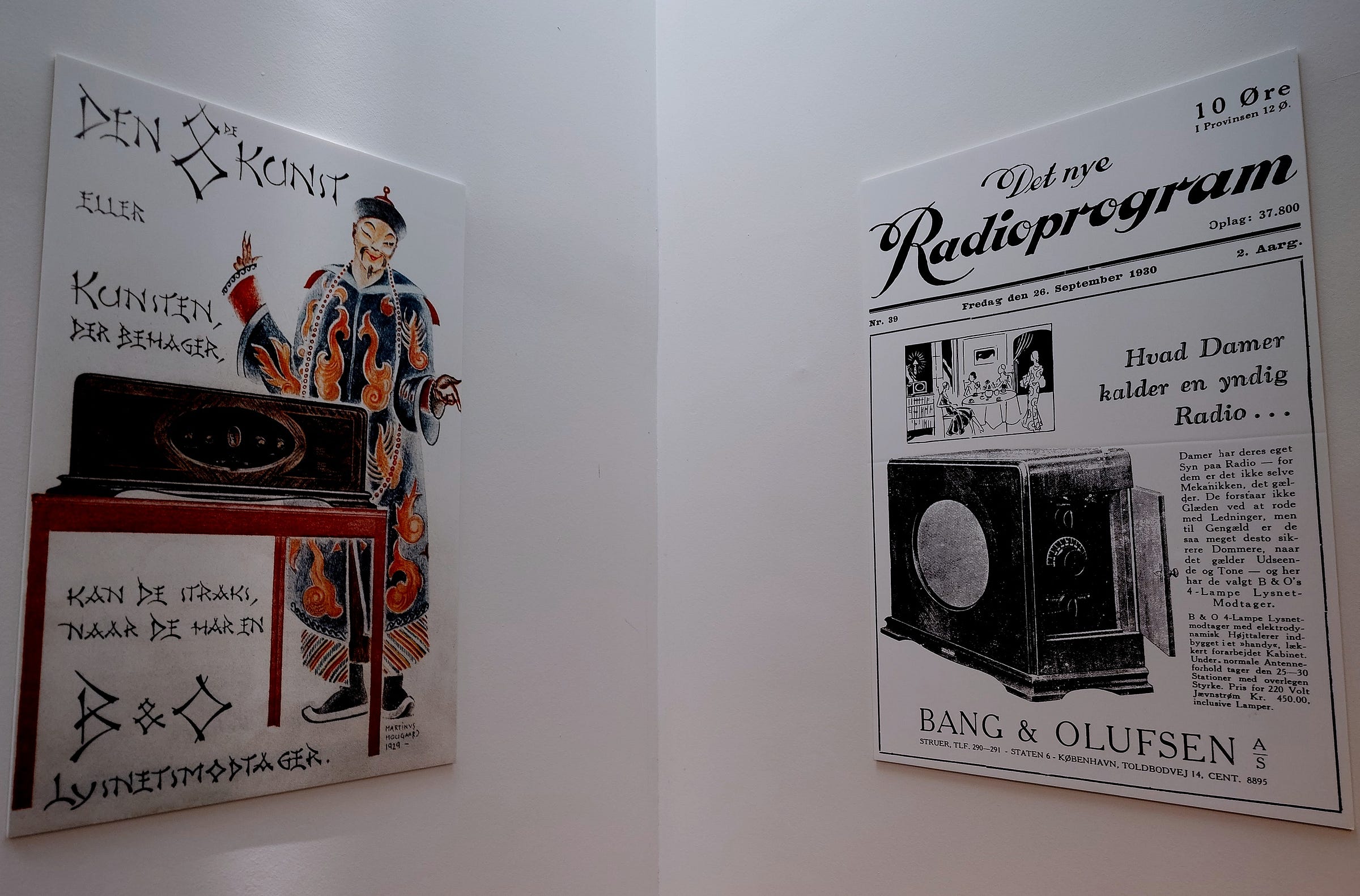

A. Friend: I visited the Struer museum days ago, the woman working there, to the woman working there, I asked enough questions that she pulled this out [I brandish a book written in Danish about the history of Bang and Olufsen], and she says you have to have this- although it's in Danish.

Was that a piss-take to you, all of the Bang and Olufsen focus in the Struer Museum?

Nikolaj: I didn't know that there was such a thing, actually. But my mom actually worked at the Bang and Olufsen factory.

A. Friend: She worked at the Bang and Olufsen factory?

Nikolaj: Everyone worked at the Bang and Olufsen factory.

[[We talk about economic protectionism, which I’ll spare you.]]

A. Friend: What were the venues in Odense that you could play at? Or was it house shows?

Nikolaj: No, we didn’t do house shows. I think we played at the old studenterhus [[translating something that really didn’t need to be translated for me:]] the student house, it was a very nice studenterhus we had back in the days, there’s a new one now..35

A. Friend: Did you go to that same private school for your whole childhood?

Nikolaj: My whole school period, until ninth grade, yeah. Then I went to the gymnasium.36 We played at the student house, which was a really gritty, raw, nice place .. but also kind of, like, falling apart, so we had to take it down at some point.

We also played at a funny place called the mimeteatre. Do you know, like, um, how do you say that in English?

[[As he says this I had no idea what it meant, because the word, as spoken in Danish, sounds like “meema” in English orthography.]]

A mimer is somebody .. often with white makeup .. [starts feeling the walls of an invisible box in front of himself] ..

A. Friend: [[realizing]] Oh, he’s a mime. We have mimes.37

Nikolaj: In Odense, we had a mimer who had a teater, you know, that's a funny thing, but sometimes he would also allow us to make a concert.

A. Friend: Did it go well when you played?

Nikolaj: I don't know, for most of my life, I've been playing with groups that rehearsed so much and we were so much in rehearsal space and recording .. but not really rehearsing for performance.

We would also always, like, do things in the last minute, like, ‘oh, yes, this also needs to be on stage tomorrow,’ so every time I played it was always with a strong, beating heart. But we managed to get through okay.

A. Friend: So describe the band setups that you guys would make, because I know you had a drum-machiner, you had somebody that you've described on the album as playing only ‘laptop,” —

Nikolaj: Carl Emil. Yeah, I went to boarding school and met Carl Emil, and he was very much into - he was a bit older at that time - electronic Danish music from Rump Recordings, like Karsten Pflum or Rumpistol, acts working with glitch and electronics.

So, he had started to study that on his own, taking samples and then starting to remix and reproduce. He would do magic in his dorm and, yeah, I was already very much into electronic music, so I was like .. that was amazing.

A. Friend: When you performed, would you route a mixing board through an interface and have him live remixing? or did he just not have a live role..?

Nikolaj: I don't think it was very advanced, we need to ask him about how he did it, because I wasn't part of it anyway. But he was definitely touching a few buttons at least. I would do most of the playing on synthesizers, guitars, and stuff, and then he would do the beats and the glitches and everything else.

A. Friend: Would you layer live drums on top of drum loops?

Nikolaj: Yes, exactly. And then sometime at a later point, Alexander [Helskov Jørgensen], my friend who was also part of our old post rock band, he would come in and put some bass lines. And also he was part of mixing and composition, stuff like that.

A. Friend: .. [[counting them out]] .. We’re up to four members of the band.

[[we both laugh]]

Nikolaj: It's a difficult time stretch [to remember] because Carl Emil and I.. we worked as a duo for some time, but then after boarding school we got home.

I got home to Odense and my old friends who I played music with, they also needed to play. So Jens [Marl Christiansen], who's the drummer for Quiet Sonia today, he also became a part of it. Jens is like, I have a very intuitive emotional approach to musicmaking, he has a more theoretical and academic approach. So he was extremely good at, like, making funny algorithms and working with indeterminacy, is that how you say it? [[I nod]]

He was very interested in a lot of more, yeah, theoretic approaches.

A. Friend: Did he use modular synth or did he use DAWs to, like, approximate?

Nikolaj: So today he's heavily into modular synth, I cannot remember if there's anything featured on [The Pink Sea]. That's a good question. But he would often also compose some stuff by programming it out. Not in DAWs, but in this way where you write string parts and stuff like that [Sibelius composition software], and he would write some piano parts. So that was a very nice balance, and contrast, to my approach.

A. Friend: So you guys would have multiple laptoppers on stage?

Nikolaj: No, on stage I think we would only have one because Jens would be behind the drums.

A. Friend: Alright, so you would have double-drumming.

Nikolaj: .. [[realizing at last]] Oh, yes! We would have half a drum kit and a full drum kit.

And then Jens Aagaard would, perhaps, also have a couple of synths as well. And Rasmus [Jon Lundager], who is playing in Quiet Sonia, he would also be playing organ and percussion and stuff like that. So there's a lot of people who have been involved in this.

A. Friend: So you had an easy time making music but a hard time recording it into songs?

Nikolaj: I think, already at the boarding school, we had these .. like five or six compositions, but that was my main curse.

The fault is primarily on me. Instead of saying, ever, that something is finished, I would constantly rework, rework, rework. And they would be totally different songs, so we had so many versions.

But the funny part of the story is that for a long time we had zero clue how to mix. Because Carl Emil, he started focusing more on his own project, Carlis38, and we were left with the laptop.

So, okay, we could record, but we couldn’t do anything else. So actually one day we took these compositions at an early stage to Jonas Munk.39

And he was like — I hope he said ‘I really like it,’ but he was like - ‘you guys need to learn how to mix.’

‘You need to think of it as a building,’ you know, with different layers and levels.

A. Friend: I have no idea what you could mean by ‘you need to think of it like a building.’

Nikolaj: Yeah, of course it's both about arrangement, but also about EQ and stuff like that. And now comes the funny part: we were an electronic band that didn't know about stereo. We hadn't discovered stereo at this point.

So after we've been at Jonas’ place, [[he starts laughing]] we would rename all of our tracks, after working on it, like “stereo mix,” because now we were able to pan things. We hadn’t panned anything before. So.. that really helped.

[[we both laugh]]

We did get back together in 2015.

A. Friend: Had you already lived in København, then? because you've mentioned that you went to university here. How did that work out?

Nikolaj: Yes.. how did that .. [[we both laugh]] ..

At some point, our friend Tobias Frank, who used to play drums in Sunn Paw, he was mixing for other people, and he works as a sound technician today, and stuff like that - he was a great asset. He had a small studio where we could mix and we could record some of the dubs, stuff like that, and we worked for maybe a year ... I was still maybe running in circles having a hard time finishing things.

A couple of years would pass and we would meet again. I remember we met in a summer house on Fynen somewhere, and we worked on it a bit more, and uh …

… we drank a lot of Fernet-Branca, and worked all night. And when we woke up, we were just crossing our fingers that it would be good. Then the years just passed again.

A. Friend: … so the final release version?

Nikolaj: One day I just .. a year ago or something, this is a boring story but you need to have it - I sort of used my newfound skills to remaster or master the tracks. And then after another long time I just, one day, chose to write to the other guys ‘maybe, should we just …’

Nikolaj: If you're interested in Danish experimental music culture, we had a collective called, like, Af med hovedet40 [literally: “off with the head”]. They came from Svendborg, and they moved together into an industrial building, pretending to be a company of some sort, in Amager, and they created a collective called Henning Young41, and they made a band called Synd og Skam.

[ ... / … / … ]

While they were having their collective in Svendborg, we had our own music environment in Odense, and it was sort of like .. modernism versus post-modernism going on, in these circles, because we were very concerned about listening to tons of different music, but still also prioritizing subjectivity and looking inwards. Personal writing. Trying to find and express some sort of, what would you call, like phenomenological artistic truth. … or, this whole concept of truth in music- not Truth with the big T but … maybe small.

That quality is something that really separated the new Odense music scene from the Svendborg scene, they were much more in the post-modern way of thinking, like playing with identities, eradicating subjectivity..42

A. Friend: As much as I like personal writing, capital-tee Truth scares the hell out of me. I think somebody's trying to sell me something.

Nikolaj: Yes, the word truth.. it's just, well, the question: do you prioritize the artistic work [in itself], or do you prioritize the process. We were, and still are, prioritizing the work .. though you can definitely do both. The folks in Synd og Skam, they're very avant-garde in essence, always trying to stay ahead of the curve ..

A. Friend: I remember reading a book43 where a protagonist was smitten with this French 19th-century writer’s quote, to some effect that ‘one must be in all things absolutely modern,’44 I just think .. what an unhelpful phrase.

Nikolaj: A very nice quote about this is, ‘what's new today will very quickly have a tendency to become the old.’

A more positive rendering of Odense’s music came when Nikolaj wrote:

“I can’t remember if I mentioned the Hindsholm Lo-fi Festival, but it was a really important festival for the underground music scene in Odense. We organized it ourselves on Nordfyn over a few years - around 2011 to 2014, something like that.

I haven’t been able to track down a poster where we played as My Tjau is Kapow, but I’ve attached one where we played as The Sea Inside a Shell (the successor to My Tjau, the predecessor to Quiet Sonia.)”

There are private worlds of comments to be made about many of these acts; only two of them are honored in any depth within this article, perhaps three if we count The Sea Inside A Shell. Many of them, I’m sure, I would discover a minor archive problem if I tried to research. Alexander Julin wrote for his website Passive/Aggressive, about the Hindsholm festival,, just once in 2012. He did a brilliant job.45

I translate a shred of his sentiments:

From the 13th to 15th of July, while the internet stood on standby, and the summer so slowly began to threaten in earnest, I chose, with a few friends, to take at trip to Fyn - more precisely Hindsholm - to take part in Hindsholm Lo-fi Festival. For me, the trip functioned as an alternative to Roskilde Festival, and it’s safe to say the feeling of community, which I’d missed at times on my trip last year to Roskilde, certainly was fulfilled this year in the Morten Korsch-esque landscapes.

In an email, Nikolaj attached a few nostalgic photos. He also sends me Love in a Dream by Scared Crow (Kasper Aagaard).46 I now know: this is my favorite act from the scene.

Love in a Dream is in places so profoundly reminiscent of Papa Sprain’s indie period music - at least my favorite bits of it - that it shocked me. Scared Crow’s songs were built up out of tiny, tinny loops, brittle and bell-like guitars, the warm-colored noise of nothing at all, bass without drums. From the depths of a cavernous reverb escape Kasper’s voice, by turns a gothic baritone - evocative of all the relevant imagery, the spread wings of a swan - and a Jens Lekmanesque twee affect.

It is, yes, a dispatch from a dream. I decided it’s the kind of thing I write about.

Nikolaj: After playing noise rock for a couple of months, again, we discovered post-rock- Godspeed [You Black Emperor], Tortoise, and a lot of Icelandic music as well. In the earliest days, I really liked Sigur Rós. I listened a lot to Múm. Do you know them?

A. Friend: I love Múm. When you listen to them, are you thinking of them as ambient, IDM, or what? When I listen to them it’s, like .. rhythmic music pushed so far that it barely feels musical per se. It feels like fabric. They are amazing.47

Nikolaj: I think a lot of more experimental, and often quite melancholic, rock music back then, probably it was after Kid A, bands began experimenting with electronics …

A. Friend: I think of a lot of bands who made releases, like, 2 years after Kid A as being Kid A bands [[Nikolaj laughs]] but I just love that. I love it when a band has a Kid A album.

Nikolaj: Yeah, to be honest, I think with electronic music there's such an unhealthy fetishism for newness, like imagining some sort of linear progress. I think it's a shame. I think just because something sounds vintage, or it's connected to a certain time period in sound and style, it doesn't necessarily mean it's bad. I think a lot of the glitch stuff that happened, there in the early oughts, ..

A. Friend: Are you thinking of Oval?

Nikolaj: He's one of my biggest musical heroes, as well, because I think he manages to do two things at once. … He’s a very radical and innovative musician- but he never lost touch of the emotional necessity in music.

A. Friend: Right, it starts from songwriting… that first album [Wonton, 1993] even has singing on it, and everyone online hates the singing on it.

Nikolaj: My favorite of his is the process album [Ovalprocess, 2000], because it's basically the most brutal, post-rock black metal .. but with glitch.48

A. Friend: The first album [Wohnton], it reminds me a lot of Bernhard Fleischmann.

Nikolaj: It's funny, I sort of had a small personal connection to that scene, also, because we have this .. Godfather figure in Odense, Jonas Munk.

A. Friend: Right, so, I certainly had planned to ask you this - is he easy to get to know, or was he just an inspiration to you growing up?

Nikolaj: Well, I was very good friends with his younger brother.

A. Friend: There we go. I take it he’s a far younger younger brother.

Nikolaj: Yeah, but I didn't really get to talk with Jonas back then, he wasn't living at home anymore. He was sort of this mythological figure for us -

A. Friend: But now he has a studio in Odense, right?

Nikolaj: Yes, since then I've often [visited], for instance I had some classes at Rhythmic Music Conservatory where I could choose [subjects] myself, and I would have conversations with Jonas about different music industry stuff. But he was connected to Morr Music and Darla.49 Also that was, I mean, we just couldn't believe this when we were younger, but he played with the Cocteau Twins50, and he had friends in Tortoise.

A. Friend: Yeah, my god. So you probably had heard the Chicago-Odense ensemble,51 was that your introduction to the Chicago scene stuff?

Nikolaj: Yeah… they began releasing a bit later- we were already all about Tortoise in eighth grade. I remember the first time I listened to Tortoise, it was I think the 2004 album, It’s All Around You.

I was pushed away from them because it’s, to my ears, it had this sort of library music, almost muzak quality. They [made] it too lush. But at the same time, they were playing with texture on that album. Today, maybe it’s my favorite album of theirs, I could still hear some really interesting things happening in that album, and also emotion, but the emotion is very well hidden under a shiny surface aesthetic. I felt like I needed to know what's going on here.

When I came to them, I was coming from listening to lots of instrumental, progressive rock music, but it was more of the virtuosic stuff. Tortoise were very, very restrained, with very tight compositions, so it was something else entirely.

A. Friend: They're such a weird band, Tortoise, my favorite song of theirs by far is the title track on TNT, they double drum on it and modulate the drumming so heavily, it’s hard to grasp what is supposed to be the core idea. […] Having the double drummers, it’s like they’re stacking these melodies and countermelodies, at all times, all these little plateaus in the drumming.

Nikolaj: Our biggest dream, you know, the noise rock band evolved into a post rock band, and then from a Godspeed You, Sigur Rós type post-rock band, over to this sort of, um, Brian Eno, Tortoise, Do Make Say Think thing… our biggest dream was to record at the SOMA Studio in Chicago with John McEntire.52 We would rehearse, I mean, every day, all the time - sometimes we would rehearse before school, like seven in the morning.

A. Friend: I'll just jump into Quiet Sonia by asking you the worst question I can: do you mean for it to sound like Swans, or Angels of Light?

Nikolaj: I think I'm the only one in my friend group who prefers the Angels of Light, above Swans. Or, no, I think Rasmus may also appreciate it. I think How I Loved You is one of my all time favorite records.

A. Friend: It's really good songwriting, always the song comes through.

Nikolaj: Yeah. But I mean, of course, it's a matter of taste. I appreciate the early Swans records and stuff like that. But I'm a bit too soft to really take it in.

[ … / … / … ]

A. Friend: Although you get gloomy, you don't necessarily get that gloomy in writing for Quiet Sonia.

Nikolaj: Yeah.

A. Friend: When you write a song, do you write chord changes out, do progressions just coalesce?

Nikolaj: This new album, it's actually the first time I've been doing it [composing]. [[laughs]]

Even though I went to the [Rhythmic Music] Conservatory … I always would, like, close my eyes, and close my ears, every time people were trying to teach me these things.

But Frida [Rolskov Pedersen], who plays the piano, is studying organ at the classical music conservatory, so she's very great. And Rasmus [Jon Lundager] has also studied music science, so I have great people to help me, transparently, and we're doing it this time, because I want a string quartet on the next album.

A. Friend: When I was re-listening to the [Wild and Bitter Fruits] EP, I noted the instrumental tracks are all mixed together very smoothly.53 You coalesce the mix together into a form where it all sits for the entire song; or I feel that the surface tension is very low, in other words. I think it’s that quality of having started with tonal richness that makes the song work as you effect the mix. […]

Reading about Talk Talk54, I feel this is quite like what he [Mark Hollis] did. He would have songs written out and have people perform them in isolation, then use the studio to distort it into a new form. And I suppose I also think the same processing form is present in TNT by Tortoise.

Nikolaj: Yeah, yeah.

A. Friend: I guess you have to have good ingredients, as a precondition to doing these things with them.

Nikolaj: One major difference to consider, there, is that both of the songs were written in advance with acoustic guitar, and there was actually violin all over the place, which did not end up on the record.

I mean, I was at the music conservatory when recording Wild and Bitter Fruits, so I had unlimited access to all of the instruments, and all of the rooms at all times, the best recording I've ever done. And I will never, probably, have that situation again, so I was just like, I'm going to take advantage of this. I was saying to myself, this is perhaps the only time in your life where you can do this completely fucked up, manic, overdub process.

A. Friend: I'm going to do the "You're going to love Fearless" thing again55, but she certainly has chapters lined up about how Loveless, Spirit of Eden, and the David Sylvian LPs, she lumped them together as, basically, bankrupt your label albums, because in every case it was that they were given far too much access to studio time, to instrumentation.

Nikolaj: Exactly.

A. Friend: And they never wanted to master it out.

Nikolaj: So, I think it's very heavily .. at least the last track in the "Weeping" is very dense, very concentrated, .. and I think I counted at one point there were just over 200 electric guitar tracks alone. [[I laugh pretty hard]]

So...

A. Friend: It doesn't sound that dense. What are you doing with the 200?

Nikolaj: It's things you cannot hear, in the background, you know … layers.

A. Friend: Is it mostly so that you have one take, and then you start finding the take bad? So you put in a new take, and then you smooth the two into one another?

Nikolaj: It's all the different melodies and fragments. And then, of course, I killed most of it, because you have to, to make it audible. It’s like a Tetris building.

I remember when I pitched This Tender Violence to the press, a lot of people were also scared of the use of silence. There's also parts that're not busy at all. So, actually, some people were a bit confused also about that.

A. Friend: Just confused about sparseness, about the existence of dynamics.

Nikolaj: Yeah, exactly.

A. Friend: Well, people just want to hear Nirvana again, I guess.

Nikolaj: [laughing] Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. And it was way too long before the vocals and the drums kick in, you know.

A. Friend: Yeah. How do you feel as a bass singer? You weren't a singer for bands before, were you?

Nikolaj: No. [...] I've had a hard time really finding, feeling comfortable in the fact of being a singer, because I played instrumental music for so many years.

A. Friend: I think that's why Angels of Light are a strong thing to bring up, he uses bass singing so well alongside guitar. And I guess he balances it for you, by always working with higher singers, as well. But I’ve recently been just looking out for bass singers and asking how they’re working around it. Do you have others that you like?

Nikolaj: [with absolutely no delay] Stephin Meritt, definitely. When I went to boarding school, I became pretty fanatic about The Magnetic Fields for many years. And, even though they’re not as popular today, I think that The National’s records around Boxer and Alligator were really great. […] I think Aidan Moffat from Arab Strap is also a big- I would maybe not say inspiration, but I listened a lot. I’ve been thinking about, when he’s performing live, how that must be difficult. He sings over electric guitars, and his spoken word and vocals are so low.

A. Friend: Are these all your favorite singers?

Nikolaj: Well, I love Robbie Basho but I don't think I will ever be able to do what he's done. I don't think it would necessarily sound very nice if I tried to. I think he's almost able to sing as expressive as he's playing the guitar. And, the same thing, I think I appreciate singers who are able to do things that I cannot do, like Tim Buckley, also has this very tense vibrato. I think another important person to mention might be Mark from the American Music Club. In my high school years, they were probably the bands I listened to the most, and the band that inspired us .. sort of a combination between them and an old 80s band called The Waterboys, this connection between, sort of, slowcore, shoegaze, dream pop, and acoustic folk rock.

[ … / … ]

Many years ago I also started experimenting with American-primitivist guitar, and stuff like that, but at that time it also felt quite new. It wasn't such a crowded and populated scene, but since then a lot of American-primitivist guitarist has surfaced, and I don't know .. I need to make sure that I can contribute something that feels necessary.

A. Friend: Also in Fearless56, there’s the story of Cul-de-sac’s album Epiphany of Glenn Jones, which they did with John Fahey. It's amazing, […] I think what's so inspirational about John Fahey, above and beside all else, was the way he bent the blues and the studio, both, to make his own expressions.

Nikolaj: Definitely I respect and admire John Fahey, but for me it’s still [Robbie] Basho. And some of the Basho-inspired guitarists, James Blackshaw is probably my favorite.

A. Friend: When you referred, earlier, to reaching out to the press about Quiet Sonia, what's that like? What do you think of the position of music in regard to state support, and how does the press’s role relate to that?

When I look into a Danish band, today, they’re really often being written about by the Danish P- channels57 — do you feel that state-funded press in Denmark just end up writing in the manner that we do in America - this fundamentally unserious, major-label-centric approach to music-writing?58

Nikolaj: You need to remember this, now, if you don't know it - the greatest, and only, zine covering experimental alternative rock music, Undertoner.

It has existed since, I think, 2002 or something. It's driven voluntarily by mostly young people in a shifting team. Without them, we wouldn't have any coverage.59 [[REDACTED WIDELY-READ DANISH MUSIC WEBSITE]] has never done anything for us.

So, um, your question was something more like can the state change its approach to music?

A. Friend: Right, or, I suppose the question is also how can music get away from this commodity model, because right now the nominal revenue of the whole industry is held by a couple Swedish guys.

Nikolaj: Yeah, exactly .. I think at least we need to soften up our categories, like it's not fair or right to think that rhythmic music necessarily has the ability to compete on the free market. It’s a very non-realistic, fundamentally wrong way of thinking. I still think there's some, which I also saw when I started at the music conservatory, there's still this, like, subconscious hierarchy of music genres where jazz music is placed higher, and then and classical music is placed above jazz, with maybe opera at the very top. I mean, can a lo-fi guitarist recording at home be just as artistically valuable as free jazz?

Of course, we have the Statens Kunstfond60, the biggest state controlled artist grant, that is being given out every year, but it .. almost always goes to the same artists, every year, those who have, you know, some kind of hype around them. […]

So I’m feeling very, you know, confused about it, because on the one hand I'm very proud that we have this state support for musicians, and artists, but on the other hand I think they need to look very closely at their criteria.

A. Friend: Of course it's always gonna be funny to me, because I just come from one of the cultures that .. loves to just stop funding art in general.

Nikolaj: Yeah, but we .. acknowledge it as a necessary part of culture, also with the public service TV channels .. everybody knows [for example] that the dogma [Dogme 95] movies wouldn't have happened without state support.61

A. Friend: It's kinda few of them that are Danish, weirdly.

Nikolaj: I know, actually a new bunch of Danish directors are trying to adopt a new dogma manifesto, now, let's see how that goes. I can see the relevance, in these days shaped by A.I. …

A. Friend: I was just thinking about Dogme because I’m reading a book on audio philosophy, and it keeps reminding me of the Dogme criteria that you should report audio from one microphone62 … I’ve just started agreeing with that part.

Nikolaj: I realized that the only way out of that loop with My Tjau was to start working with dogmas. QS’s dogmas was to use one take. It has to be live recorded, and only [acoustic] instruments.

[ … / … / … ]

I was so fascinated by how you recorded in really old days like you have these tape machines, you have limited space, limited tracks, it puts so much pressure on the musicianship to be at the highest level. I'm not saying that we reach that point, I think it could definitely have benefitted from some overdubs, but the challenge of trying to make a live, first-take, over the [typical] freedom of recording in a rock environment, that prioritizes something extremely different.

A. Friend: I think room recording has to be explored further, it's just … people don't love it enough.63

Nikolaj: Exactly. I was thinking about Godspeed! You Black Emperor, who always recorded live, also.

A. Friend: Steve Albini was perhaps pro room-recording in the same way, he was very against algorithmic reverb, and for room reverb.64

Nikolaj: Rest in peace.

A. Friend: Rest in peace.65

Thank you to Nikolaj for room-recording with me in a single take. I added artificial reflections in post. Thank you for reading.

I can’t wait for Quiet Sonia’s next album and will drop a link here the minute that I can. I hope you’ll enjoy 2023’s QS like I am.

In a certain sense it’d be right to say that his whole life has gone into that album, a statement which maybe he’d quietly detest.

Frederiksberg is, on certain levels, held to not be in København, although Frederiksberg is in København. It’s a Lesotho-South Africa relationship, except that both are in Denmark, and various other differences. Article about it.

Why the Danish "København" for Copenhagen? Because most of the other anglicizations of Danish endonyms sound very weird to me, to the point where I frequently forget that some anglicizations exist. So, most of my endonyms will be Danish, though I don’t want to say ‘Danmark,’ which sounds almost exactly like Denmark if you say it correctly. (My rule is ‘don’t make a style guide,’ so a little contradiction is a sign of health.)

I’m not gonna link everything every time Nikolaj mentions Jens Aagaard, who it is pretty contextually evident he loves, but, yes, Jens is a drummer (to that end you can sample him?) and electronic producer and much else who makes releases as Tettix Hexer. Resident Adviser calls him a “well-known face” as long as you’re in the underground scene of Odense and/or Copenhagen, and I feel like that last part is true, actually, because here’s him playing with Croatian Amor for Janushoved’s anniversary concert.

I’m not sure what possessed me to think this was a good question. Almost all Danes went to folkeskole, which is just the name of their public school system, which originates in the early 1800s (and Danes would like me to point out that ‘schooling is optional, but education is mandatory’).

It worked out: Nikolaj fits into the approximately 1/6 of the Danish population who went to private school, or ‘friskole’ as they say. My mother and her siblings, actually, are another example- she says “it was a tradition that my family went to friskole, my family was rebellious in their own .. country kind of way, learning at their own pace, rather than conforming in large classes .. that country type of stuff was part of the reason I moved away ..”

(And, indeed, she moved first to København, then Aarhus.)

I wish I knew which song he means specifically, here, but fortunately/unfortunately the Danes wrote whole songbooks of Danish folkesang about atomkraft, you know, how it’s bad, or portentious. The Netherlands-based website Laka, which focuses on the archive and documentation of the history and culture around nuclear power, described and archived many Danish anti-atomic-power songs here.

This is a rather extreme position Nikolaj is taking, in giving this answer. Poul Lendal has at least his own 2005 LP Ønskebarn [literally: wish-child], and played with the 1970s Danish folk group Fynboerne [literally: ‘the residents of Fyn’]. I feel fortunate to be able to tell you that Lendal is also part of a folktronica duo called Vaev, today. They have been active for a decade or so.

I have found one video interview with Poul Lendal from 2018 online, which is one of many interviews hosted by Danmarks Rigsspillemænd with their membership of honored folk musicians. From what I understand, he speaks about his father playing harmonica, and then the village musicians who he heard growing up, and who he played with in learning fiddle. I think he says that most of his playing vocabulary comes from these village players, and that one fundamentally plays with life when it’s what they’ve heard from others.

I also found an independent writer going as ‘A Green Man’ reviewed the aforementioned 2005 LP, in the process referring to an interview Lendal must’ve done with something called the Global Village Idiot. I appreciate their attention to fiddling traditions and passion for the music.

Fanø’s folk music seems to have been described by some ethnomusicologists as being derived from Polish folk music, and is reliably described as having existed with ‘unbroken traditions’ for over three centuries. The music is passed through generations to be performed by groups on holidays, and the songs are treated as sacrosanct. Two forms of dance and song reliably mentioned are Sønderhoning and Fannik. The former comes from Sønderho on the South point of the island, while the more generally-named Fannik comes from Nordby, where the ferry arrives to Fanø from Esbjerg, and where about 7/8 of the population of Fanø live. The village of Sønderho’s old city preservation foundation [[translating loosely]] published a writing about their folk music, with songs embedded to hear; and they also point to a particularly excellent writing on Fano’s folk musics by Denmark’s Royal Library’s Living Culture project. The Danish String Quartet has enjoyed some success in recording original performances of Sønderhoning folk, and in the process releasing scores for purchase.

The current music library in Odense is the immediate neighbor to the current main Odense railyard, and it was Odense’s old main railyard, which opened in 1914 (functioning at that point as a sort of ‘overflow’ railyard, so to speak, ancillary and addressing the overloading of the original railyard), it ceased railyard functions in 1995 and then reopened as the new music library in 2013. Danish TV2 Fyn has an article from 2013 about the decision for the ‘old railyard’ to be repurposed into the music library here. There is a now-defunct Wordpress blog dedicated to interesting libraries and they wrote a resource page about the history of the music library here. The actual tourism board for the city of Odense wrote about the old railyard here.

I’ve been trying to find some kind of research that I could share with you all about how weird it is that Odense has a great music library, because it’s the only music library I’ve ever been to. I think it must be one of very few dedicated ones in Denmark. The Danish group of music libraries is organized under the heading “dmbf” (Dansk Musikbibliotek Foretningen), they don’t have a functioning website. They were probably in the international association of music libraries (thusly acronymized called IAML), but they left the organization in 2022.

I’m not really sure how well the music library is doing for itself in this streaming era (or perhaps in 2025 we’re in the deathspiral of the VC-overfunded streaming era which succeeded at little other than destroying the ostensible value of digital audio files).

I noticed while reading about the current music library that there must’ve been a minor public spat when the studenterhus took over this building because it was unclear where the music library would reopen. It’s also written about very plainly in this Fyens Stiftstidende article from 2013, with no sense of melodrama conveyed. Syddansk Universitet published a writing about the original studenterhus and its operations here.

I knew Balloon Magic, so of course I bragged about this to Nikolaj.

Balloon Magic made pretty strong jangly indie pop, you know, the stuff that sounds like The Smiths (or Aztec Camera, or Josef K, perhaps Orange Juice? - whatever they’d want me to say). I’ve listened to their song Waking Up quite a lot. Their solitary EP Mornings was released by very long-running indie-pop label Shelflife, and so Balloon Magic are immortalized as family with the likes of Airiel, Pinkshinyultrablast, and The Radio Dept.!

The biggest complaint I have is that they stopped. They truly are a band with 4 good songs.

(Actually, every time I think about Balloon Magic, I then think about the Swedish band Days who did basically the exact same thing in 2008, releasing one lovely jangly indie-pop EP through Shelflife Records and then calling it quits. Oh, and I just noticed that another Swedish indie-pop band that I like called Kuryakin made the very next Shelflife release.)

I certainly knew nothing of Tobira Records before this interview. Randomly, while chatting with Nick Keeling, he mentioned he’ll soon go to Japan, and while there he’ll play live at Tobira. So Tobira’s musical radar, it must be said at least, reaches the very best outskirts of mine and supports the people there. Nick gave me that Tobira’s owner is Taka, and that Taka does a radio show for Popeye. Here’s Nick Keeling performing there.

Actually, I find it illustrative to share the following unbelievably impressive navigation section which the Tobira Records website comes outfitted with, even though I fear it won’t read very well on a phone screen (maybe you’ll be able to pinch-zoom into there):

I feel as though prying a bit, trying to find the nominal interviews with Jonas in which he is still a child, but yes, it checks out very quickly that people were paying attention to Jonas’s opinions on music when he was a child.

Jonas’s ambient music has been released under such names as Franciska and Forankring, non-exclusively speaking; and Jonas runs (makes?) afvikling kassetter [afvikling means withdrawal, settling, giving up, abolition, etc.]. Not all of afvikling’s releases are from himself and friends, perhaps, I don’t see clear evidence of that but that’s what discogs’s description said. I ordered some cassettes from blacklight in Aarhus, among them 3 from the label Pladeselskabet Pladeselvskab, which you’ll find is also the work of Jonas, and these tapes are nowhere to be found online, and the one that is online was released by 4 other unnamed labels, which I suppose evidences an unobservable network of minor cassette makers in Denmark, too small to be named, or not to be.

Perhaps this is a bit of a foolish anglophone thought. Denmark uses “kunst” for the realms which we might call “fine art” in English.

I must write the word in italics, even though it needs no translation, because the Danes say it so Danishly. Sources online have me believe that American Lutherans have this, too.

Many of my Danish family were eager to tell me their stories about their confirmations. Already in the 1980s, my aunts and uncles were all functionally godless. My mother remembers the children of her village would, if I remember the story correctly, spend about a week camping in the yard of the village pastor in anticipation of their confirmation, she remembers this as a good time, though the whole while she was rejecting his arguments for faith.

It’s of course a minor tragedy, the kind that I write about here, that Geiger fell off the web, it is very hard to search for Falkenstrøm’s writing specifically.

I was able to find the 69 by A.R. Kane review, written by him, just bumbling around aimlessly on the archived version of geiger.dk; I enjoyed his writing there, which is commanding and evident of the attitude of someone with a PhD in avant-garde literature, who gives teenagers Bark Psychosis records.

Speaker Bite Me were an indie rock band, I guess it should be said, which had some really interesting ambitions across their entire career. I have just realized while writing this footnote that Speaker Bite Me are actually the kind of band that I reach out to, indeed the only result I get when searching for an interview with them, online, is this 1999 blurb.

Bows were a Too Pure artist, the union of Signe Høirup Wille-Jørgensens with Luke Sutherland, who Nikolaj is about to mention in the interview, and some other musicians playing more limited instrumental roles. Unfortunately I haven’t found a text, yet, which pours out very much ink about Bows. They released LPs in 1999 and 2001, both are good; I prefer the latter, Cassidy. The credits for Cassidy suggest that Luke played most of the instrumental roles, and now I realize this is a story for a different article.

Signe is now recording actively as Jomi Massage. She is still great. American hipsters reading might be excited to learn she made a split single with ML Buch in 2016.

The Rhythmic Music Conservatory is such a brilliantly named thing that when Nikolaj said it to me, during the interview, I thought he was making a Freudian slip, because I had said “rhythmic music” earlier. I’m going to stop myself from trying to find something really brilliant to share with you about the institution, because I’ve noticed when I search for writing about it that it’s currently receiving a decent sum of coverage because of alumni like ML Buch, Fine, Molina, Astrid Sonne, Erika de Casier, etc., and I think just on that short list I must’ve named the majority of Dean Blunt’s contacts in Denmark. Tone Glow has an interview with Molina where she mentions Sonne and Buch as her classmates here, and on the same note he interviewed Sonne here, though the schooling didn’t come up.

Luke Sutherland is perhaps most often known as the singer for another Too Pure artist, the inimitable, breathtaking, intoxicating, alluring, genderflexible, post-dance musical thing Long Fin Killie. That band’s career is actually described pretty well on Wikipedia. To this I will also note that I’ve only just noticed that Luke was a frequent contributor (here’s the band posting him recording violin) to at least the studio recordings by Mogwai (here’s him performing with them live), and indeed the two bands are listed together in the few writings I’ve been able to find regarding a post-rock scene in c.2000 Glasgow, in which Mogwai are a titan but Long Fin Killie also very highly regarded. They were a band that really managed to install (within “indie rock”?) a unique and expressive, tense, fragile beauty, the warmth and rhythm of nightlife, the immediacy of privacy.

Luke Sutherland went on from Long Fin Killie and Bows to be part of a trio called Music A.M., who had a Deutsche website and released 3 LPs onto a Belgian label called Quatermass. The trio was made up of Luke along with Volker Bertelmann (who made independent releases as Hauschka before playing with Music A.M., the duo Tonetraeger, et al., and since then has gone on to a very successful career as film composer) and Stefan Schneider (whose other main platform I’d like to note was the downtempo-IDM-rock(?!) group To Rococo Rot). Of the Music A.M. releases, Nikolaj mentions it’s Unwound from the Wood, from 2006 (Forced Exposure provide a short treatment of it), that he listened to most. (I think the opener on Unwound from the Wood is unreal, “Always.”)

Electrelane are another late-90s Too Pure records band, a bit of a refrain in these footnotes. Some of Electrelane’s releases can be found on Bandcamp through Beggars Arkive. Electrelane were comprised of only female musicians, and they only released good albums, though Scaruffi’s judgment differs from that statement slightly. Brooklyn Vegan says they’re back together, or they were in 2021.

Mikael Simpson is pretty famous in Denmark for being a radio DJ. He also was the guitarist for Luksus, who were good.

Unfortunately, there are so many interviews with Graham Sutton, and Talk Talk is mentioned quite religiously within these interviews, I’ve been unable to locate one where Sutton talks about the experience of actually hearing Talk Talk for the first time, it was in any event before Sutton was 14. I believe much ink was spilled in Jeanette Leech’s Fearless [Jawbone Press, 2017(, will be mentioned in every interview I do)] about the members of Bark Psychosis being strung along by an older session drummer (named John Ward) who claimed to have been Talk Talk drummer Lee Harris (read about it here, too), and befriending Lee Harris after writing him about this topic … I told Nikolaj all this later that afternoon, immediately before we walked through Assistens cemetery. We’d invented a thing where we both bought 2 beers from the 7/11 without having lunch.

There is a studio called Dustsuckersound, which I feel confident enough to suggest must be Graham Sutton’s house. From there, as Nikolaj says, he’s contributed production to albums by [British] Sea Power (perhaps someone reading this will need this information: this group produced the soundtrack for Disco Elysium), but also Delays and Coldharbourstores.

Nikolaj was not kidding when he said “right now” - These New Puritan’s new album Crooked Wing was released on the day of this interview, with Sutton among three credited producers.

Wow. That was easy. Fyens Stiftstidende has an article showing the vacated Galaxy Net Cafe in 2020, behind a paywall.

I’m sharing this memory because it makes me happy.

I anticipate that this is generally true of cities in countries with primate city population distributions, of which Denmark is a significant example.

The last-such railway-ferry in Denmark was the Rødby-Puttgarden line (I enjoyed reading about the decay of the line in this 2019/20 article), which shuttered in 2019, leaving only two such ferries in operation in Europe, both a little more tenuously slated to cease operations. Perhaps a land trip from Berlin to Odense is presently far more troublesome than when the line ran, however, construction began in 2021 on the Fehmarn Belt fixed link, an immersed tunnel which hopes to connect northeast Germany to Lolland, where automobile traffic will then obviously route for København.

See footnote #9.

The idea of gymnasium corresponds roughly to high school in Denmark, and a lot of the other Protestant nations.

I mean, we don’t. But the cultural text of American adolescence includes the cultural fact that mimes exist, vaguely, especially in France.

Carlis at least played Loppen in Christiania one time in 2012, or perhaps more impressively was played on a public radio station >= 37 times. He’s also on the poster in the footnote that follows, playing with Manual.

Jonas Munk is perhaps, in the eyes of both Nikolaj and myself, the most successful Danish musician we mention. Actually the first time that Nikolaj mentions Jonas Munk, in the real order of the interview, is when he says ‘in Odense we have this godfather figure named Jonas Munk…’. Jonas Munk makes releases as Jonas Munk and Manual and is in Causa Sui, today, and many other projects he’s worked on are worth your ear.

I don’t have the story of the first time Nikolaj played with Jonas Munk, which could’ve been this show that Nikolaj sent me the poster for:

Munkemøllestræde 20 was, it seems, just someone’s apartment; google maps archeology makes it seem like that building must’ve gone abandoned for several years between 2009 and 2019, by which time it had been replaced with a handsome multifamily residence with feature windows. Anyway, this address is about 50 paces away from the childhood home of Hans Christian Andersen, which is a half-timber building serving as a museum, not to be confused with “H.C. Andersen’s House,” the other, much larger, museum devoted to him in town, where tickets are kinda mad expensive.

I knew nothing about the collective except for the existence of Synd og Skam. But, I soon learned that it includes the band First Flush (interviewed in english here). Af med hovedet collective also included Bankerot, which is the solo project of Bjarke Valentin Pedersen, whose 2020 release Vampyr I dearly love. (Vampyr is one of multiple Bankerot releases for Kornmod, who I will surely be writing a footnote about, soon, so I guess scroll down a little to see that.) Bjarke seems to have no online footprint outside of his releases, but passive aggressive published an essay on him and Vampyr in 2020, by Joalane Mohapeloa, so I am heartened to excerpt their words:

Bjarke Valentin mestrer en sjælden ærlighed, og han formår at få det til at lyde som om, at det ikke kan lyde anderledes (!). Kærligheden er dansk, hverdagsagtig med lange mellemspil, fra et mandehjerte, som forsøger at elske sig ind i voksenlivet:

uh du går

jeg ses med dig senere og vi kysserjeg beder dig om at lade det dage

jeg beder dig om at lade det dage

jeg beder dig om at glemme det jeg sagde

Here’s Anne Moller writing for Undertoner, in 2012, about Henning Young, which she describes as a spillested in Amager. She writes of the bands that played, and, yes, describes some as having a l’art pour l’arte approach. I am warmed by the following statement:

Ølkortet koster 50 kroner, og for dem får vi 11 øl. Hver af dem markeres ved, at et nummer prikkes ud på bagsiden, så det foto, der er på forsiden efterhånden er fuld af huller. På vores er et ældre ægtepar afbildet, og de er snart indkredset af elleve udbulede huller.

Nikolaj’s guide to the Svendborg scene, for me, included highest praise for Synd og Skam’s 2015 EP Blafret Ør Af Kjoler, and similarly for the same year’s LP Sidste Fantasi, each of which can be found online and each of which strains any categorization I might impose on it in a word, in places assuming the form of a jagged, shambling, unique post-punk, moments of brassy nocturne (“New Note”), distorted and deranged popsongs that connect by turns to mid-80s pop and mid-00s R&B (it’s “Sværmer Sværmer” I have in mind). Some of these songs I can feel have been perhaps undercut just a touch in searing originality in the intervening decade.

On First Flush, his adoration was most for their 2018 Spira, where the band draws more on folk timbres - and on this note I can feel some level of kinship between the sound of Quiet Sonia and that of First Flush, as on “Laissez-Faire” - and, in Nikolaj’s words, high-poetic lyricism (I’m still a long way from being able to form judgments of Danish lyricism as I hear it). There is nothing exceptional in my drawing the previous comparison, as the release features Thea Thorborg on violin, who is of course violinist for Quiet Sonia (and partner to Nikolaj, and I am also thankful to her for letting me into their apartment). Thea played also in the folk ensemble called Värmland-forsamlingen af 2016, whose three releases were only in one case made in 2016, the one which I listened to a few times was 2018’s Musica.

Time is temperature, temperature is a media problem, and the website for the record label Visage, which picked up where Af Med Hovedet left af, is already an unhosted domain. Visage made releases by each of the artists thus far mentioned, in many cases helpful descriptions of the works which can still be accessed on archive.org, and in at least one case they made a record label compilation. Here we have reached, assuredly, a topic for another Absent Friend.

The Baudelaire Fractal by Lisa Robertson, I think. It has its charms.

Rimbaud: “one must be absolutely modern,” he’s purported to have written. At least that’s how it’s translated by Paul Schmidt. Rimbaud didn’t live for a day outside of the 19th century, so at least I got that part right.

Alexander Julin, whose photos of Hindholm festival I am co-opting here, took lots of great photos of the type that you would’ve seen on tumblr at the time [Grimes warning].

Kasper is brother to Jens Aagard, who is Tettix Hexer. Nikolaj consistently footnotes that moniker beside Jens’ name when speaking.

I just read PR copy for the band described them as just an “atmospherically driven Icelandic band.” They are kinda an ambient group, they kinda build their songs around drum loops, but thusly neither feature really functions as such.

I’ve listened to this album a few times and always think about this statement, ‘black metal’ being used as an intensifier. I liked this 2013 ‘Innerversity’ interview with Oval’s Markus Popp in which he described Ovalprocess as the first album of his to demonstrate how the creative process of an electronic music is inextricable from their software tools, which is kind of a deflationary remark in light of the things both I and Nikolaj were saying about him having a songwriterly slant. In this video interview from 2006 for Salon(!?) he describes the dialectic at play as being between aesthetic ideas and structural elements. The same is perhaps even more starkly demonstrated by this 2010 interview, conducted by Dan Rule and also published by Cyclic Defrost, that Popp says only recently had he “said ‘I’m going to be the musician now and I’m going to play my own music.’” I don’t know— I certainly feel that there can be no missing level of emotionality and soul on the album imparted by its condition as process music. I’ve long felt more intensity and intention is conveyed to me from this kind of song-form than from conventional songwriting. He put it that way in the video interview: even in this structural music there is still always the authorial question of what the work will ultimately ‘convey.’

(As a total aside, I’ve just noticed Ovalprocess was released by Thrill Jockey. Everywhere I go in writing for this website, that place ends up being Chicago.)

Alright, beyond the two hyperlinks, I’ll provide some words on Morr and Darla, here, and perhaps I should’ve ordered this whole piece in a way that would’ve put this footnote further up. These are household names in this part of the musical world … but I really didn’t know anything about Morr Music until a few years ago when I decided to get into ‘indietronica’ and realized the term has very little use outside of the orbit of this label, who have already been a key name in multiple of my interviews.

Since 1999, Morr Music have been an essential label for the late-90s-to-early-00s culture which we might today called indietronica, in their words “the intersection of indie pop and electronic music.” I could just as well espouse their importance for ‘alternative electronic,’ ‘leftfield electronic,’ or the branding they attempted to create for themselves: Plinkerpop (people attempting to use the term; typification of its meaning is included in this review and this review). It was actually not Morr Music that coined the idea of Indietronica, but they’ve made releases by, or featuring, most of the artists on that compilation.